My name is Nikolai Petrovich Gromov, I am 56 years old. I have been working as a ranger for eleven years now. Eleven winters, eleven springs. Almost four thousand sunrises over the forest, which I know better than the lines on my own palms.

Before this, there was another life, completely different. For twenty-two years I wore the shoulder straps of an investigator for particularly important cases. I started back in the Union, as a young lieutenant. Then the city, the regional department. I solved murders when others threw up their hands. I had commendations, medals, the respect of colleagues. I thought I was serving the law. I thought I was making the world cleaner.

And then the Kharitonov case happened. Even now, after so many years, my jaw clenches when I remember it. There was this entrepreneur in our city — Kharitonov Vadim Sergeyevich. From the “new” ones, those who rose up in the 90s on whatever came to hand. Shopping centers, car dealerships, connections in the administration. And he had a terrible habit. He loved very young girls. He broke lives.

One of them couldn’t take it. 19 years old, a first-year student. She stepped off the ninth floor of her dormitory. She left a note. In the note was Kharitonov’s name and details that made my hands shake, even as a seasoned investigator. I opened a case, collected evidence. Found three more victims who agreed to testify. Everything was concrete. The statute, the term, justice.

And then the general called me in. I won’t retell that conversation. I will only say that I left the office with a clear understanding: the case would be closed. Kharitonov was a sponsor of the right people. A friend of the right families. Untouchable.

And so it happened. The charges were reclassified, then dropped altogether for lack of corpus delicti. They made Kharitonov’s security guard the scapegoat. A quiet guy, a former paratrooper, whose wife was sick and who had two children. Allegedly, he drove the girl to it. Allegedly harassed her. The poor wretch didn’t even understand what was happening when he was given eight years in a strict regime colony. I saw his eyes in the courtroom. I still see them.

That evening I got drunk for the first time in fifteen years. Came home, sat in the kitchen, and drank until the bottle was empty. My wife… Ex-wife. She looked at me from the doorway and was silent. By that time, we were already living like neighbors. She had long wanted a different life, different money, a different husband. Someone like Kharitonov, probably. A month later she filed for divorce. I didn’t argue. I wrote my resignation report the same day I signed the divorce papers. My length of service allowed it. 22 years. Lieutenant Colonel. The pension was small, but enough for bread. I sold the apartment, bought an old UAZ, and left.

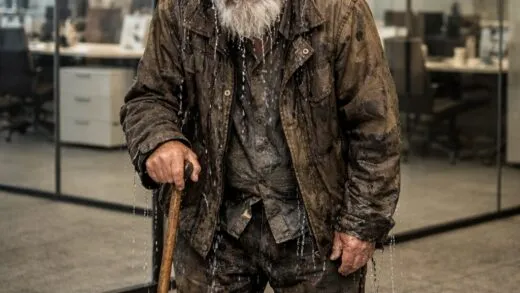

At first, I didn’t know where myself. Just away from people. From their lies, their money, their rotten souls. The forest didn’t accept me immediately. The first winter I almost died. From cold, from stupidity, from lack of skill. But I survived. I got a job as a ranger in a nature reserve. They were just looking for a person for a remote cordon where no one wanted to go. Three days’ journey from the nearest village. Communication only by radio, and even that was sporadic. Electricity from a generator. Water from a stream. Paradise.

The first years I was simply silent. I only talked to Uglyum. That’s my dog. A West Siberian Laika. Grey and black. Smart as a human, only more honest. I took him as a puppy from some animal abusers I arrested in my third year of service. They wanted to drown him. Said he was defective — didn’t bark. And he really doesn’t bark. He only growls when he senses danger. But he picks up a trail in a way that would make any bloodhound envious.

Gradually, I began to thaw. Not my soul. My soul, probably, remained frozen in some places. But the anger went away. That black, sticky anger at the whole world that burned me from the inside for the first years. The forest drew it out, took it for itself, dissolved it in the infinity of swamps and spruce forests.

Here I learned to breathe again. To wake up not from an alarm clock, but from the light. To fall asleep not from fatigue, but from a honestly lived day. My cabin, two rooms, a Dutch oven, a porch overlooking the ravine became dearer to me than any city apartment. The smell of birch logs, the resinous spirit of cedar, the tart bitterness of lingonberry leaf in tea — these are my joys. Simple. Real.

Every morning I patrol the territory. In winter on skis, in summer on foot or by boat along the Chizhapka. I check the feeders, salt licks, watch out for poachers — unfortunately, there are no fewer of them. I keep track of the animals, write reports, contact the office by radio. Sometimes I host hunters, legal ones, with licenses. I show them the grounds, make sure they don’t violate the rules. The work isn’t dusty, but it’s not simple either. The forest does not forgive mistakes.

I have a few more lodges in the territory. Hunting huts scattered through the forest at a distance of a day’s march from each other. The base one, where I live permanently, and three distant ones, for patrols. The furthest one is on Rotten Lake, almost at the border of the Reserve. I get out there two or three times a year to check if it has fallen apart. It’s such a wilderness there that even poachers don’t go. Swamps all around, only I know the trails.

I thought I had seen everything in this life. Injustice, betrayal, human baseness in its vilest manifestations. And then — silence, peace, redemption through labor and solitude. I thought I had found my shore, that I would live here until the end, and the forest would accept my bones as calmly as it accepts fallen leaves. But what happened last autumn changed everything.

October that year turned out warm, Indian summer dragged on, the mosquitoes hadn’t disappeared yet, and in the mornings the fogs were such that you couldn’t see anything three steps away. I was just getting ready for a long patrol, to check the lodge on Rotten Lake before winter. Uglyum was spinning under my feet, poking his nose into the backpack, asking to go with me. He always senses when I’m leaving for a long time. I took him, of course. Without him in the forest, it’s like being without a hand.

We walked for two days. We spent the first night in the intermediate hut on Crooked Creek. Everything was in order, only the roof had sagged a bit, would need patching in the spring. I planned the second night already at Rotten Lake. I was hurrying. Wanted to get there before dark, before the fog covered everything.

We reached the lake towards evening. The sun was already setting behind the spruce forest, painting the water in dark gold. It was quiet. Not a breeze, not a bird. Only mosquitoes ringing in my ear — the last ones of the year. And then Uglyum stopped. He never barks, I said. But when he senses a human, he freezes, fur standing on end, and watches. That’s how he stood, looking at the lodge.

I followed his gaze and froze myself. Smoke was coming from the chimney. A thin grey stream, almost invisible against the evening sky. Someone was heating the stove. In my cabin, which is seventy kilometers through the swamp from the nearest habitation.

First thought — poachers. They broke in, the bastards. They think no one will find them here. But we’ll see about that. I took the carbine off my shoulder. A “Tiger,” semi-automatic. Chambered for 7.62. Reliable machine, bailed me out more than once. Clicked off the safety. Signaled Uglyum to stay close. We went around, through the spruce forest, to approach the cabin from the rear.

I crept up to the window. The glass was cloudy, dirty, but you could see through. What I saw made me freeze.

Two women were sitting at the table. One, older, forty-something, broad-shouldered, with short hair. Even through the dirty glass, I could make out tattoos on her hands. Blue, prison ones. She was saying something, leaning low towards her companion. The second one was quite young, almost a girl, pale, with dark circles under her eyes. She was wrapped in some rags and trembling slightly, either from cold or fear. Both were dressed in grey robes. Government issue, crumpled. Prison uniforms.

Fugitives. From a transport or a colony — what difference does it make? Escaped convicts in my lodge 70 kilometers from the nearest habitation. What are they doing here? How did they even get here? Through the rotten marshes, where even I pass with difficulty, knowing every bump?

There was no time to think. The instruction clearly states: upon discovery of fugitives — detain, report by radio, wait for a squad. No improvisation. They could be armed, dangerous, unpredictable.

I went around the hut, stood by the door. Deep breath. Uglyum beside me, tense as a string. I kicked the door open and stepped inside, raising the carbine.

— Don’t move! Keep your hands where I can see them!

The young one screamed, reacted with fright. The older one — differently. Slowly raised her hands palms forward and looked at me point-blank, without fear, with some heavy, weary doom.

— Calm down, father. — Her voice was hoarse, low, smoky. — We are not armed. You can check.

— Shut your mouths! — I didn’t lower the barrel. — On the floor, face down, both of you!

The young one sobbed, began to slide down the wall. It was clear she was barely standing on her legs. The older one didn’t move.

— Listen, ranger… You are a ranger, right? We haven’t done anything bad to you. The door was open, it’s damp there, the lock rotted. We didn’t touch your food, just fired up the stove. The girl is in a bad way, understand? She needs warmth. — She shook her head. Slowly. Wearily. — You can shoot. You can call a squad. But listen first. Ten minutes. Then do what you want.

I looked at her over the sights. Tattooed fingers, sinewy hands, a scar on her cheekbone. People like that usually don’t beg. People like that either fight or run. Only now did I get a good look at the second one’s face. God. Just a child. Twenty, maybe twenty-two. Big eyes, sunken cheeks. Hair dull, matted. And the look of a hunted animal that knows there is nowhere to run.

Something clicked inside me. Something I thought had died long ago.

— Ten minutes, — I said, not lowering the carbine. — Speak.

The older one closed her eyes slightly — either from relief or gathering her thoughts. And began to speak.

— Shoot, father, or listen. There is no third option.

She said these words later, when I had already listened to the end. When everything inside me turned upside down. When I realized that these ten minutes would change the rest of my life. But more on that later.

I stood by the door. The stove crackled, casting reddish reflections on the log walls. It smelled of smoke, dampness, and something else. Sour, sickly. That’s how a person in a fever smells. The young one slid onto the bench, hugged herself with her arms, and stared at the floor. Trembling with a fine tremor. This wasn’t a game. This girl was sick. Seriously sick.

The older one, the one with the tattoos, stood opposite, still with her hands raised. Calm as a rock. Only her eyes were alive, sharp, watching my every movement.

— Speak, — I repeated. — Time’s ticking.

She slowly lowered her hands. I twitched the barrel:…

Comments are closed.